Rana Plaza was an eight-story commercial building on the outskirts of Dhaka, Bangladesh where five garment factories made clothes for major brands across the world including the U.S., UK, Spain, Italy, Germany, and Denmark.

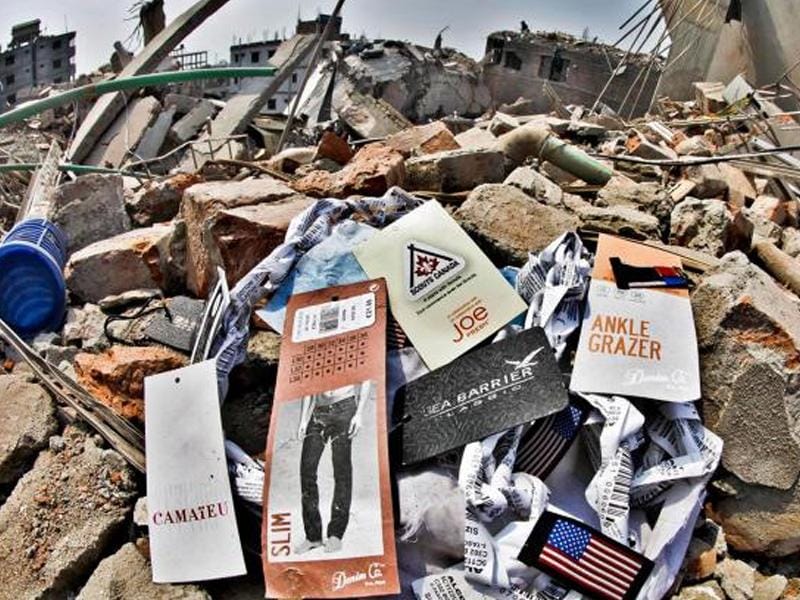

In April of 2013, the Rana Plaza building collapsed, killing 1,132 people and maiming more than 2,500 others. This tragedy became a symbol of the fashion industry’s impact and need for sustainable reform.

April 24, 2021 marks eight years since the Rana Plaza disaster.

This series, created in partnership with sustainable fashion leaders at Dhana, will provide a comprehensive look at the social, environmental, and economic impact of the fashion industry, much of which provided the underpinnings for the Rana Plaza disaster.

Each year, the Rana Plaza disaster reminds us of the work needed to recognize and redefine the impact the fashion industry has on the world. With global reach, the industry has the unique opportunity to make positive change if we commit to fulfilling that potential.

This post is our launching pad where we are going to:

- Introduce you to the avoidable tragedy at Rana Plaza; and

- Explore what has been done since the collapse to address the working conditions and protection of workers in the fashion industry.

What Happened at Rana Plaza?

Rana Plaza was in Dhaka, Bangladesh, one of the largest clothing-producing cities in the world. The city hosted roughly 5,000 factories. 85% of the factory workers are women who support their families with an average of $50 per month.

On April 23, 2013, garment workers were removed from the Rana Plaza building when cracks appeared in the building walls. The owner relayed, however, after an engineer inspection, the building was structurally sound.

The next morning, workers continued to express concern about the safety of the Rana Plaza building as cracks cut through weight-bearing structures of the building: the walls, pillars, and floors. Many told management they didn’t want to enter the building because of the deep cracks. Still, management ordered garment workers to their usual posts inside, threatening their jobs and pay if they refused.

Early in the workday, the power to the building cut off, the cracks widened, and concrete fell onto workers sewing, buttoning, and fastening clothes. It took less than ninety seconds for the eight-story building to collapse and kill 1,134 workers and maim more than 2,500 others.

Images and videos from the event are very disturbing. People were trapped under the fallen structure, many dead and many still alive calling for help. The gruesome images of their friends and coworkers under the collapsed cement as well as witnessing their own injuries left many survivors with not only permanent physical injuries, but severe psychological trauma. Some lost limbs, slipped into comas, or require daily medical attention to this day.

Rescue workers and volunteers spent weeks searching for bodies, some losing their own lives in their attempts to save garment workers trapped under the rubble of the factory building.

**This video from the New York Times shares photographs captured by a man in Dhaka during the Rana Plaza disaster. It contains graphic images and video some may find disturbing.**

What Was the Cause of the Rana Plaza Collapse?

A number of engineering and administrative failures contributed to the ultimate disaster of the Rana Plaza garment factories in Bangladesh. Experts have since concluded the garment factory collapse was “entirely preventable.”

Parts of the building were constructed without proper permits from the city. The fifth through eighth floors were added onto the building without supporting walls. The heavy equipment from the garment factories was more than the structure could support. The foundation was weak, built on swamp land. As the cracks deepened, the building was destined to cave in.

While these failures explain the collapse of the building, it’s the failure to respond to known dangers that caused the deaths and injuries that came with it. Despite garment workers being coerced back into the building, the bank and shops located on the lower levels did remain evacuated due to the dangers of the cracks discovered the previous day. Garment factory management was as aware of the risks as the banks and the shops were.

Unfortunately, factories’ interests in filling orders came before the safety of those doing the work.

Rana Plaza & Fashion’s Wake Up Call

The Rana Plaza disaster brought worker safety in the fashion industry to headlines around the world, from The New York Times to The Washington Post and BBC.

What Companies Were Involved in Rana Plaza?

Some of the fashion brands manufacturing in the Rana Plaza garment factories during the collapse were Walmart, The Children’s Place, and Primark. This wasn’t the first garment industry accident, but its severity and preventability launched it into the spotlight.

Rana Plaza demonstrated the impact of the fast fashion industry.

When the focus is on rapid production, garment workers are forced to produce high quantities for Western brands paying low rates for clothes they will sell for cheap prices.

In the 2015 The True Cost documentary, factory owner Arif Jebtik explains that when brands approach factories, there is a notable power imbalance. Brands negotiate prices, always having the option to go to another factory that will do the work for cheaper if yours won’t do it. Undercutting costs comes at the expense of the worker.

“They’re selling [a shirt] at $4, so the target price is $3. If you can make that $3, you are getting business. Otherwise, you are not getting [business]. Because we want that business so badly and we are not getting other options, ok.”

For more on the origins and rise of fast fashion read: The History of Fast Fashion.

What Were the Effects of the Rana Plaza Collapse?

After the collapse of Rana Plaza, a number of initiatives were founded to emphasize the urgency of ethical working conditions for the garment industry and compensate the families affected by the tragedy.

Local and Legal Response to the Rana Plaza Disaster

Energized by a need for change, relatives and community members of the victims gathered at the site to protest unsafe working conditions and demand more responsibility and accountability from factory employers.

Local courts in Bangladesh put 41 factory managers on trial for murder and related charges due to decisions that may have led to the Rana Plaza disaster. Sohel Rana, the owner of the Rana Plaza building, was arrested and remains in jail on a number of other charges, including breaching building codes. The murder trials have yet to begin due to delays in legal procedure.

In May 2013, the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh was signed by 220 companies.

The Accord called for immediate action on an implementation plan that required safety inspections, safety training, and remediation of dangerous conditions in garment factories. Hugo Boss, Espirit, Mango, and American Eagle Outfitters are among the 2018 signatory groups.

Advocacy organizations called for compensation of victims. With the help of the Rana Plaza Arrangement, some families received compensation to help cover medical expenses and loss of income associated with the collapse of the garment factory.

By 2015, $30 million was paid out to family members and victims of the disaster funded by donations from individuals and fashion brands. Much of the distributed funds were directed toward medical bills incurred from the disaster. With large portions of survivors left permanently injured, both physically and emotionally, many have been unable to rebuild their income to liveable levels or return to the financial situation they’d risked their lives for working at Rana Plaza.

International Response

Global organizations took action to create safer working standards in the garment industry. The UN International Labor Rights Forum and Human Rights Watch are two NGOs dedicated to advancing policies that protect workers and enhance working conditions that advocated in the wake of Rana Plaza.

Since the Rana Plaza disaster, at least 109 more accidents have taken place according to the International Labour Organization (ILO). Factory fires and building collapses are still the reality for people working in clothing factories in low-income countries where brands outsource production.

Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic solidified many of the issues faced in the fashion industry and, in many ways, halted progress made.

In March 2020, it was reported that several large fashion brands were refusing to pay for fulfilled orders. The #payup campaign was launched to demand corporate accountability for the estimated $40 billion worth of inventory ordered, fulfilled, but not paid for.

By summer 2020, $15 million had been recouped from brands like Gap and Zara, but millions of garment workers were still laid off due to the pandemic without pay.

Consumer Response

In part due to the tragedy at Rana Plaza, various consumer-centered movements have brought attention to the working conditions involved in the manufacturing of our clothes.

In 2014, Fashion Revolution incorporated the hashtags #whomademyclothes and #Imadeyourclothes to raise public consciousness of the working conditions in fashion. During the very first Fashion Revolution Day #whomademyclothes became the number one global trending hashtag on Twitter.

Since its inception, the annual event has continued to gain momentum. In 2018, 3.25 million people took part in Fashion Revolution’s week-long initiative to draw attention to supply chain transparency.

Customers fuel Fashion Revolution’s advocacy. With consumer support, Fashion Revolution’s extensive Transparency Index grades brands on their supply chain ethics, largely dependent on their traceability and transparency. This keeps standards high and public awareness even higher.

Although there is some progress to celebrate, we have a long way to go for consumers, retailers, and governments, to combat the harmful working conditions being faced by garment workers to this day.

And so, if reality still hasn’t changed for garment workers around the globe…what can be done?

A Push for a More Ethical & Sustainable Fashion Industry

The Rana Plaza disaster triggers a larger conversation about how our purchases impact the livelihoods of others.

While institutional change is a must in the garment industry to protect workers in Bangladesh and beyond, as consumers, we “vote” with every dollar we spend (or don’t) on clothing.

We can choose to support brands that respect the dignity of workers, prioritize the health of the planet, and use their business to do good. And, we can choose not to support brands that fail to meet those minimum standards.

A more ethical and sustainable fashion industry can exist. In some instances, it already does.

Fashion as a Vehicle for Change

I see the Rana Plaza disaster as a somber call to action to redefine the impact of fashion. This event and its anniversary tether us to the ongoing conversation around changing fashion for the better.

After all, fashion is the only industry that touches on all 17 Sustainable Development Goals. Our task is to make sure that its impact is a positive one.